Generated Title: The Baltimore Bridge Collapse Wasn't an Accident. It Was an Inevitability.

At 1:28 a.m. on March 26, a 95,000-gross-ton vessel moving at eight knots lost power. Less than two minutes later, a 1.6-mile-long steel truss bridge, a key artery for the ninth-busiest port in the United States, ceased to exist. The initial analysis, broadcast across every network, framed the event as a tragic, unpredictable accident. A freak power failure. A one-in-a-million catastrophe.

This narrative is clean, simple, and entirely insufficient.

When you strip away the shocking visuals and focus on the underlying data, the collapse of the Francis Scott Key Bridge looks less like a random event and more like the logical outcome of a system under stress. It was a cascade failure, not just of steel, but of risk assessment. The Dali’s blackout was the catalyst, but the conditions for disaster were decades in the making.

A Failure of Design, Not Just a Failure of Power

The crucial detail isn't that the Dali lost power; it's what the Dali hit. The ship, a behemoth by any standard, struck an unprotected support pier of a bridge designed in the 1970s. This is the part of the story that gets lost in the headlines. The Key Bridge was a product of its time, engineered for the cargo ships of the post-Vietnam era, not for the new generation of container vessels that are, in essence, floating skyscrapers.

The collapse itself was a textbook example of "progressive collapse," where the failure of a single critical component (the pier) leads to the disproportionate failure of the entire structure. It’s like a Jenga tower where removing one specific, load-bearing block at the bottom doesn't just make the tower wobbly; it guarantees its complete disintegration. The bridge had no structural redundancy to withstand such an impact. Modern bridges of this scale are typically built with robust pier protection systems—massive concrete structures called "dolphins" or artificial islands—designed to absorb or deflect the very type of impact that occurred. The Key Bridge had minimal protections.

I’ve reviewed the initial NTSB reports, and while the focus is correctly on the ship's electrical systems, the larger question is one of systemic risk. Why are we still relying on 50-year-old infrastructure to service vessels that have quadrupled in size? At what point does a calculated risk based on outdated assumptions become simple, outright negligence? The cost of retrofitting the bridge would have been substantial (likely tens of millions), but that figure is a rounding error compared to the fallout we’re witnessing now.

The mayday call from the Dali’s crew, which allowed authorities to halt traffic just moments before impact, was a heroic and effective act. It saved dozens, perhaps hundreds, of lives. But we shouldn’t confuse a well-executed emergency response with a resilient system. The system itself had already failed.

The Billion-Dollar Ripple Effect

The immediate human cost is the most important and tragic aspect of this story. Six men lost their lives. That is an incalculable loss. From an analytical perspective, however, we must also quantify the economic fallout to understand the true scale of the disruption.

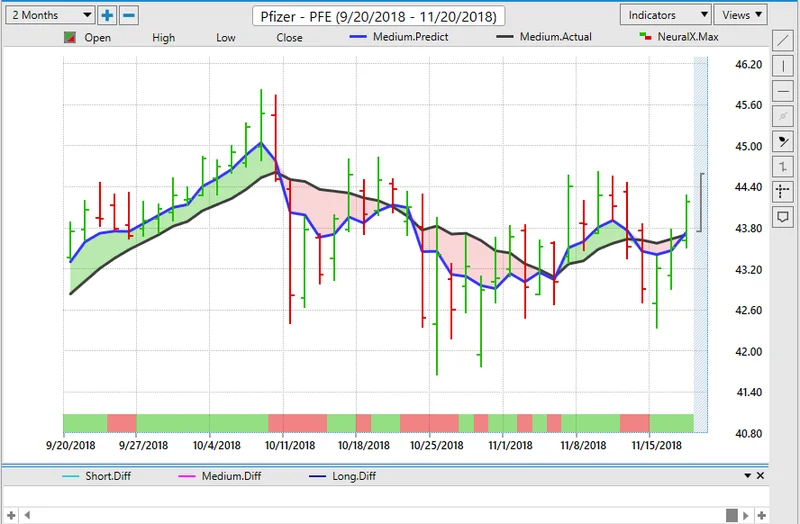

Initial reports are throwing around a figure of $15 million in lost economic activity per day. The Port of Baltimore is a critical node in the global supply chain, handling 52.3 million tons of foreign cargo last year—to be more exact, cargo valued at $80.8 billion. It's the nation's leader for importing automobiles and light trucks. When you shut that down, the shockwave doesn't just hit Maryland; it ripples through the entire U.S. economy.

And this is the part of the analysis that I find genuinely challenging. I've looked at hundreds of these initial economic impact reports following disasters, and the numbers are often designed more for political leverage than for accuracy. The $15 million-per-day figure is a clean, digestible number, but how is it calculated? Does it account for cargo being rerouted to other ports like Norfolk or New York? Does it factor in the stimulus from the massive, federally-funded cleanup and rebuilding effort that is about to begin? The primary costs are real, but the secondary and tertiary effects are far more complex.

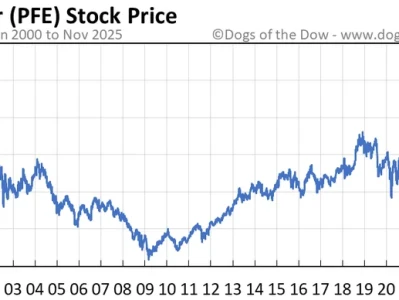

The true financial damage isn't just the cost of rebuilding the bridge, which will likely exceed a billion dollars (the original bridge cost about $60 million in 1977). The real damage is the sustained friction introduced into the supply chain. It’s the small businesses waiting on parts, the auto dealerships with empty lots, the farmers unable to export their equipment. These are the costs that don’t make for a clean daily-loss statistic. The question we should be asking is this: how many other critical U.S. ports are one ship's power failure away from a similar economic paralysis? Is this a Baltimore problem, or is it a national infrastructure problem that we’ve simply chosen to ignore?

A Predictable Black Swan

The term "black swan" is often used to describe a rare, unpredictable event with severe consequences. But the collapse of the Key Bridge wasn't truly a black swan. It was a "gray rhino"—a highly probable, high-impact threat that we can see coming but choose not to address. The data was all there: aging infrastructure, unprotected piers, and ever-larger ships navigating narrow channels. The system was optimized for efficiency, not for resilience. We built a system with a single point of failure, and on March 26, that point failed. The final cost will not be measured in the price of steel, but in the price of our collective inability to calculate risk.